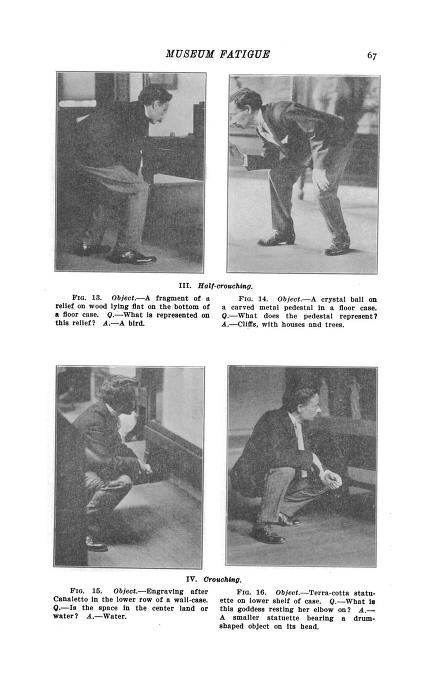

Image Above: Gilman (1916)

This post highlights some key points of visitor studies history, from Bernard Schiele’s 2016 article titled “Visitor studies: A short history.”

- The history of visitor studies goes back probably longer than you think.

The first studies emerged in the early 20th century (Schiele, 2016). One of the early writers is Benjamin Ives Gilman, whose study highlighting museum fatigue (1916) is still referenced today (renegade tour company, Museum Hack, even has a summary of the article). Gilman photographed the many different positions visitors twisted themselves into, to view the displays, and argued that this led to fatigue that could be avoided if museums altered their displays to increase visitor comfort (1916).

- Early studies were all about observed behaviour.

In the 1920s and 30s Edward S. Robinson and Arthur W. Melton carried out a series of studies that measured visitor behaviour (Scheiel, 2016: 334). Robinson recorded what he termed the visitor’s ‘external behaviour’ – which was any behaviour he could observe – and measured where visitors stopped, the duration of those stops and how they moved through the museum galleries (ibid.). Melton was similarly focused on observable behaviour and he experimented with rearranging installations, and then observed visitors, to determine which setup led to more stops and increased the duration of those stops (ibid.: 335). Both Robinson and Melton were important researchers at the time but missed the opportunity to capture information that was not observable, like visitor motivations, needs and experiences.

- Caring about what visitors think, experience and learn did not take off until after World War Two.

In 1949, British writer Alma Stephanie Wittlin’s work signaled a new direction in visitor studies; she wanted to know what the visitor was thinking (Schiele, 2016; 337) in addition to observing their behaviour.

In the post-war years, there were major changes in society which led to museums being more visitor centered (Schiele, 2016: 337). This meant that museums had to adapt to a broadening audience, with changing values in order to survive. Schiele highlights that this is when visitor studies really found “its footing” (ibid.).

With an emphasis on measuring exhibit efficiency, Harris H. Shettel pushed to make visitor studies more scientific (Schiele, 2016: 339). This meant defining research criteria and objectives so it would be possible to evaluate if the exhibit was having the desired outcome (ibid.) Of course, this means the exhibit then has to have objectives, which were often focused on learning, to begin with!

This was summed up by Chan Screven, a prominent contributor to the field of visitor studies, who called evaluation the “systematic assessment of the value (worth) of a display, exhibit, gallery, film, brochure, or tour with respect to some education goal for the purpose of making decision (continue it, redo it, stop it, throw it out, avoid it in the future)” (Screven in Schiele, 2016: 340). In short, in order to do visitor studies, you need to have an objective you know you are measuring against.

- A Canadian museum was at the forefront.

This next point is short, but exciting (if you are a museum nerd). In 1974, the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) became the first museum to “systematize the designing and making of exhibitions” (Schiele, 2016: 341). This meant visitor studies were woven into the exhibit development plans.

- Not everyone agrees on the best approach to do a visitor study.

The history of visitor studies is not a monolith. While Shettel and Screven argued for an approach to visitor studies that involved measuring outcomes based on pre-defined objectives, Robert Wolf took the opposite stance (Scheiel, 2016: 343). He was not interested in only measuring learning outcomes, he wanted to understand how the visitor made meaning of their experience (ibid.). This shows there are still many ways to approach doing a visitor study!

Over time visitor studies have become more scientific and rigorous and although some study techniques have been around for nearly a century, there is still plenty of room for growth and creativity in this field. If you work with visitors, and want to get to know their needs better, don’t be afraid to try your own study!

Sources:

Gilman, B. I. (1916). Museum fatigue. Scientific Monthly, 2, 62–74. https://archive.org/details/jstor-6127/page/n1/mode/2up

Schiele, B. (2016). Visitor studies: A short history. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure, 39(3), 331–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2016.1243834